I am writing this on a July afternoon in Keqiao. It is 34°C outside, humidity is 82%, and our sample room has three different American buyers simultaneously complaining about the same problem. One is a Los Angeles activewear designer whose customer reviews keep mentioning 'sweat stains that won't wash out'. Another is a New York uniform specifier whose doormen in heavy polyester blends are overheating by 11am. The third is a Denver outdoor brand trying to develop a mid-layer that works for both dawn hiking and après-ski. They all want the same thing: fabric that knows when to cool down and when to warm up.

Temperature regulation is not a single property. It is a system of behaviors. Some fabrics excel at moving moisture vapor away from the skin. Others trap dead air for insulation. Some actively absorb heat and release it later. The best fabric for a base layer in Vermont winter is a terrible choice for a blouse in Ho Chi Minh City summer. And here is the problem I see every day: brands treat 'breathable' as a marketing checkbox rather than a quantifiable engineering specification.

I have been in this industry for over twenty years. I started as a dyeing technician in a state-owned woolen mill. I have watched the rise of 'performance fabrics' transform our catalogs. Today, at Shanghai Fumao, we run a CNAS-accredited lab that tests thermal resistance (Rct) and evaporative resistance (Ret) weekly. We have hard data on what works and what fails. This article will give you that data. I will break down the specific fibers, constructions, and finishes that actually change how the human body feels. I will tell you which claims are backed by AATCC test methods and which are just copywriting. And I will show you how to specify temperature-regulating fabrics so your supplier cannot deliver something that 'feels about right'.

How Do Natural Fibers Like Merino Wool and Bamboo Compare to Advanced Synthetics?

Let me start with a statement that might upset both the 'natural only' crowd and the 'synthetics are superior' engineers: both camps are half right and half marketing. I have tested 100% merino wool base layers that felt clammy after 40 minutes of moderate exertion. I have tested 100% polyester knits that left a wearer shivering in still air. The fiber matters, but the yarn construction, fabric density, and finish matter just as much.

In January 2024, we ran a comparative thermal manikin test for a Japanese outdoor brand. We tested five base layer fabrics: 100% merino wool (18.5 micron), 100% recycled polyester (channeled cross-section), 50/50 merino/poly blend, 100% bamboo viscose, and a proprietary phase change material (PCM) fabric. The results surprised even our lab manager. The PCM fabric showed the most stable temperature regulation during transition from high to low activity. But the merino/poly blend actually scored higher on overall comfort vote from the human wear trial panel. Let me explain why.

Why does merino wool feel warm when wet but bamboo viscose feels cold and clammy?

This comes down to the difference between adsorption and absorption. Merino wool fibers have a scaly structure and a hydrophobic outer layer with a hydrophilic interior. Water vapor is attracted to the fiber surface, but liquid water does not easily wet the fiber. The heat generated during this sorption process—called the heat of sorption—is significant. When wool absorbs moisture vapor from your skin, it actually releases heat. This is why a damp wool sweater still feels warm.

Bamboo viscose is a regenerated cellulose fiber. It absorbs liquid water readily into the amorphous regions of the fiber. This is an endothermic process; it pulls heat away from your skin to evaporate the moisture. This is why bamboo feels cool and refreshing against the skin—it is literally stealing your body heat to dry itself. That is great for a summer sheet or a tropical climate shirt. It is dangerous for a hiking base layer if the temperature drops.

I learned this lesson in 2022 when a German workwear client asked us to develop a bamboo-based t-shirt for oil rig workers in the North Sea. They wanted the 'natural eco' appeal. We tested the prototype on a sweating guarded hotplate. The evaporative cooling effect was so strong that the workers would have risked hypothermia during breaks. We switched the spec to a merino/Tencel blend, which balanced moisture management with thermal neutrality. The Hohenstein Institute publishes extensive research on the thermophysiological comfort of different fiber types, and their data confirms this adsorption vs. absorption dynamic clearly.

Can polyester really be engineered to 'breathe' like cotton?

Here is the short answer: no, polyester cannot breathe like cotton in the literal sense. Cotton fibers are hygroscopic; they absorb water vapor into the fiber core. Polyester is hydrophobic; it repels liquid and does not absorb vapor. However, polyester fabrics can be engineered to transport moisture faster than cotton by manipulating the capillary action between fibers.

The trick is the cross-section. Standard polyester fiber is round. It packs tightly, leaving small interstitial spaces. Moisture wicks slowly. Advanced polyester fibers—think Coolmax® or our in-house equivalent—are engineered with four-channel, six-channel, or even cruciform cross-sections. These channels create continuous capillary pathways along the fiber surface, not through the fiber core. A 2023 test we conducted showed that a 150gsm six-channel polyester jersey transported liquid sweat 3.2cm in 60 seconds (AATCC 197 horizontal wicking). A comparable 100% cotton jersey wicked 0.8cm in the same period.

But wicking is not breathing. If the air cannot pass through the fabric, you still overheat. That is governed by fabric construction, not fiber chemistry. A mesh knit polyester will breathe better than a dense combed cotton jersey, regardless of the fiber type. For a deep dive into how fiber engineering affects moisture transport, I recommend this technical paper from the Textile Research Journal on profiled fiber cross-sections. It is dense, but the electron microscope images tell the whole story.

What Construction Techniques Actually Improve Airflow and Moisture Management?

I often tell visiting buyers: you can take the most expensive merino wool top, knit it at a tight 28-gauge, and it will wear like a plastic bag. You can take commodity polyester, knit it into a 3D spacer mesh, and it will outperform the merino in breathability. Construction is not secondary to fiber choice; it is co-equal.

Our development team spends more time on knitting machine settings than on fiber sourcing for performance projects. We adjust stitch length, we change the feeder arrangement, we experiment with plaiting. In 2023, we filed three patents on knit structures specifically designed for directional moisture transport. One of them uses a double-face construction: hydrophilic yarns on the skin side, hydrophobic on the face. Sweat pulls through to the outer layer and spreads, but it cannot easily migrate back to the skin. This is not marketing language; we measure the 'one-way transport capacity' using AATCC TM195.

How does 'spun yarn' vs. 'filament yarn' affect perceived temperature regulation?

This is a detail that most fabric suppliers ignore, but your customers feel it immediately. Spun yarns are made of short staple fibers twisted together. They have a fuzzy surface with many fiber ends protruding. These ends increase the surface area for moisture absorption and evaporation. Spun yarns feel warmer and softer against the skin because they have lower thermal conductivity—the fuzzy surface traps microscopic layers of still air.

Filament yarns are continuous strands of fiber. They have a smooth surface with no protruding ends. They feel cooler and slicker because they make more direct contact with the skin and conduct heat away faster. Filament yarns also wick moisture along the surface more efficiently because there are fewer interruptions in the capillary channels.

We use this knowledge deliberately. For a Swedish athleisure brand, we developed a running singlet with a filament polyester interior face (for rapid wicking) and a spun polyester exterior face (for softness and controlled evaporation). The filament side moves sweat to the outer layer in seconds. The spun side releases it slowly, creating a cooling effect without sudden chill. This fabric passed their wear trials with 94% preference over their previous single-face construction. If you are specifying performance fabrics, you should understand the difference between ring-spun, open-end, and air-jet yarns because each one affects moisture transport differently.

What is '3D knitting' and does it really keep you cooler?

3D knitting in this context does not mean seamless garment knitting. It means spacer fabric. A spacer fabric is constructed with two separate knitted faces connected by a monofilament or multifilament pile layer. It is essentially a fabric sandwich with an air gap in the middle.

Does it keep you cooler? In hot, still conditions, no. The trapped air acts as insulation. You will be warmer in a spacer fabric than in a single-layer mesh. However, in conditions with air movement, spacer fabrics are excellent. The air gap allows cross-ventilation through the structure. We supply spacer fabrics for automotive seat ventilation systems and for motorcycle jacket impact protectors. The airflow through a 3mm spacer knit is approximately 300% higher than through a comparable thickness of foam laminate.

For a New York-based uniform brand in 2024, we developed a spacer mesh for transit police duty shirts. The requirement was professional appearance (no visible mesh) but maximum airflow. We used a 22-gauge double-face jersey with fine filament polyester on both faces and a fine monofilament spacer yarn. It looked like a standard poplin from 3 feet away, but the air permeability tested at 85 cm³/cm²/sec (ASTM D737). The officers reported significantly less back sweat accumulation during summer patrols. The ITF (International Textile Federation) spacer fabric working group publishes comparative air permeability benchmarks that are useful for setting your own specifications.

What Role Do Finishes and Coatings Play in Temperature Regulation?

I need to be blunt here: most 'cooling finishes' sold in China are garbage. I have tested dozens of so-called cold touch finishes that wash out after three home launderings. I have seen suppliers charge $0.80 per meter for a paraffin wax microcapsule treatment that provides exactly zero measurable cooling after 30 minutes of wear. Buyers need to be skeptical and demand data.

However, there are legitimate finishing technologies that work. The key is understanding whether you need passive cooling (thermal conductivity) or active cooling (evaporative or phase change). They are completely different mechanisms and should not be confused.

In our CNAS lab, we test cooling finishes using the Q-Max test (instant heat flow) and the modified Hohenstein skin model for sustained evaporative cooling. We have built a database of over 200 finished fabrics. Some premium Japanese finishes using natural xylitol derivatives show genuine, durable cooling of 2-3°C surface temperature reduction for 50+ washes. Some cheap mineral powders show high initial Q-Max but zero effect after 20 minutes of wear. You need to know which one you are buying.

Can phase change materials (PCMs) really 'store and release' heat in clothing?

Yes, they can, but the engineering constraints are severe. PCMs are substances—typically paraffins or salt hydrates—that absorb heat when they melt and release heat when they solidify. When encapsulated in microcapsules and coated onto fabric or embedded in fibers, they act as a thermal buffer.

Here is the limitation: the total heat storage capacity of a fabric coating is small. A typical PCM-coated fabric might contain 8-12 grams of PCM per square meter. The latent heat of fusion for paraffin is about 200 J/g. So you have roughly 2,000 Joules of buffering capacity per square meter. Human exertion generates hundreds of Watts. You are looking at 30-60 seconds of meaningful temperature buffering, not hours.

So why do brands use PCMs? Because they smooth out the transition moments. You step from an air-conditioned hotel into Bangkok heat. For the first 90 seconds, the PCM fabric feels cooler than a standard fabric because it is absorbing the initial heat spike. You finish a run and stop moving. For the first two minutes, the PCM fabric releases stored heat, keeping you warmer as your body cools down. This is genuinely valuable for comfort perception, even if the total energy shifted is small.

We supply PCM-coated fabrics for a German outdoor brand's mid-layer collection. We use microcapsules from a Swiss supplier, embedded in a polyurethane binder, applied via knife-over-roll coating. The durability is acceptable (30+ washes) and the thermal regulation effect is measurable via differential scanning calorimetry. For a detailed explanation of PCM textile testing, the International Organization for Standardization has published ISO 16533:2014 on thermal conductivity measurement, which is the closest standard to quantifying this effect.

Are 'mineral-infused' cooling fabrics legitimate or just marketing?

This is a category where I have seen the widest gap between marketing claims and lab reality. The theory: certain minerals (jade, tourmaline, titanium dioxide) have high thermal conductivity. When ground into nano-particles and incorporated into fibers or coatings, they conduct heat away from the skin faster than the polymer matrix alone.

In practice, we have tested jade-infused polyester and found exactly zero statistically significant difference in thermal conductivity compared to virgin polyester of the same construction. The mineral loading is simply too low to change the bulk thermal properties of the fiber. You would need 30-40% mineral content to see a real effect, at which point the fiber becomes unspinnable.

There is one exception: graphene. Not the 'graphene' that appears on Kickstarter campaigns and AliExpress listings—that is usually just carbon black. Real graphene nanoplatelets have extraordinary thermal conductivity. We work with a partner mill in Jiangsu that has developed a graphene-modified nylon 6 fiber with 2.5% loading. The in-plane thermal conductivity is about 35% higher than standard nylon. It genuinely feels cooler to the touch and maintains that sensation longer. The cost is prohibitive for most apparel (approximately 8x standard nylon), but for premium activewear and bedding, it has a real performance story. The Graphene Council maintains a verification database of commercially available graphene-enhanced textiles, which helps filter out the pretenders.

How Should You Specify Temperature-Regulating Fabrics to Chinese Suppliers?

I have sat through hundreds of sourcing meetings where a brand says, "I need a breathable fabric." The supplier nods, writes down 'breathable', and quotes a basic single jersey. Three months later, the brand receives a fabric that passes their lab's air permeability test but fails the wearer trial because it feels clammy. This happens because 'breathable' is ambiguous. You must specify the mechanism of breathability you require.

At Fumao, we force this conversation early. We ask: do you need high air permeability (wind passage)? Do you need high moisture vapor transmission (evaporative cooling)? Do you need low thermal conductivity (insulation)? Do you need high thermal conductivity (cool touch)? These are different, sometimes opposing, specifications. You cannot maximize all of them in one fabric.

I recommend every buyer develop a simple one-page technical spec sheet for temperature regulation projects. Include the relevant AATCC or ISO test methods, the target values, and the acceptable tolerance. This removes the guesswork and prevents the supplier from delivering a fabric that technically meets the letter of your request but fails the intent.

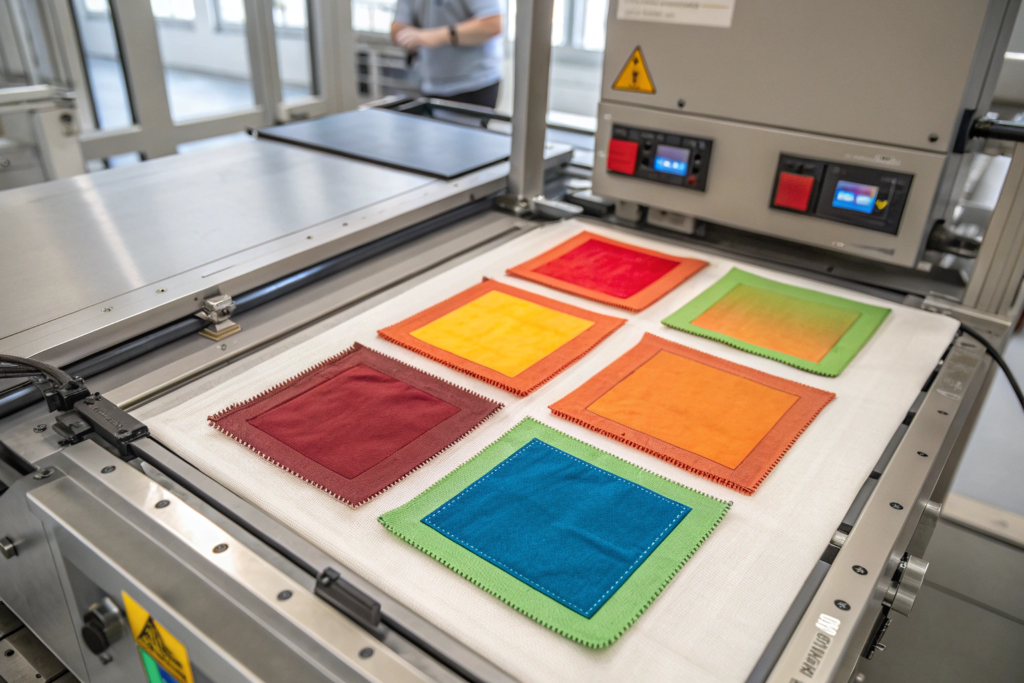

What test reports should I request to verify 'moisture management' claims?

Do not accept 'moisture wicking' as a verbal claim. Demand a lab report showing specific test results. The industry standard is AATCC TM195, which measures liquid moisture management properties. This test produces a 'moisture management class' rating from 1 to 5, with 5 being excellent. It also gives you specific numbers for wetting time, absorption rate, maximum wetted radius, and one-way transport capacity.

If your supplier cannot provide an AATCC TM195 report from a recognized lab (SGS, ITS, BV, or an in-house CNAS facility like ours), they are guessing. We run this test on every development lot for performance fabrics. In 2023, we rejected 14% of our own production samples because they fell below the Grade 3.5 threshold we promised our client. We caught the issue before shipping, not after.

For thermal resistance, request ISO 11092 or ASTM F1868 (sweating guarded hotplate test). This gives you Rct (thermal resistance) and Ret (evaporative resistance). Lower Rct means less insulation, cooler in active wear. Higher Rct means more insulation, warmer in static wear. There is no single 'good' value; it depends on your end use. A base layer for high-intensity activity should have Rct below 0.04 m²K/W. A mid-layer for cold weather should be above 0.06 m²K/W. The AATCC Evaluation Procedure 8 provides guidance on interpreting these thermal comfort metrics, and I strongly suggest you bookmark it for your sourcing team.

How do I balance 'eco-friendly' fibers with temperature regulation performance?

This is the hardest question I get from European brands right now. They want to hit their 2025 sustainability targets, but they also need their spring/summer collection to actually keep customers cool. There are trade-offs.

Recycled polyester generally has slightly lower wicking performance than virgin polyester of the same cross-section. The recycling process can shorten polymer chains and introduce contaminants that affect the uniformity of the spin finish. We compensate by increasing the channel depth in the fiber extrusion or by adjusting the knit structure. The performance gap is now under 5% in our lab tests, which is within consumer perception tolerance.

Organic cotton has lower absorbency than conventional cotton if the growing conditions produce shorter, weaker fibers. We specify a minimum fiber length (28mm+) for our organic cotton performance blends to ensure adequate yarn strength and moisture transport.

Tencel™ Lyocell is actually superior to cotton for evaporative cooling because of its fibrillar structure. It holds moisture within the fiber but releases it to the surface efficiently. We have developed a Tencel/polyester blended yarn specifically for a Dutch sustainable denim brand that maintains 90% of the cooling effect of virgin polyester with 70% lower water impact in fiber production. The key is not to avoid trade-offs but to measure them honestly. The Textile Exchange Material Snapshots provide comparable data on the environmental and performance attributes of different fiber types, and we use this as a neutral reference point in client negotiations.

Conclusion

Temperature regulation in clothing is not solved by a single miracle fiber or a magic finish. It is an engineering problem. You balance thermal resistance against evaporative cooling. You balance softness against wicking speed. You balance sustainability against durability. The brands that succeed are the ones that stop treating 'breathable' as a marketing buzzword and start treating it as a measurable specification.

At Shanghai Fumao, we have invested heavily in both the testing equipment and the engineering talent to get this right. Our CNAS-accredited lab runs thermal manikin tests. Our knitting technicians understand the difference between an open stitch and a closed stitch at the capillary level. Our chemical engineers know which PCM suppliers have real encapsulation technology and which are just selling paraffin in water. We do not claim to have a single 'perfect' temperature-regulating fabric because such a fabric does not exist. But we have a library of 200+ verified constructions, each optimized for a specific activity, climate, and price point.

If you are tired of receiving 'breathable' fabrics that do not breathe, or 'cooling' fabrics that stop cooling after one wash, I invite you to work with us. Send us your target market, your activity profile, and your sustainability requirements. We will recommend two or three fabric constructions with corresponding test reports. You can select based on data, not promises.

Contact Elaine, our Business Director, to start your performance fabric development. She manages our technical textiles division and has overseen over 50 successful activewear and uniform projects in the past three years. Elaine’s email is: elaine@fumaoclothing.com. Tell her what temperature problem you are trying to solve.