You’ve found the perfect suiting wool. The pattern is impeccable. You invest hundreds of hours into tailoring a jacket, only for the collar to buckle, the lapels to droop, or the entire structure to feel limp and cheap after the first dry clean. The culprit is rarely the main fabric. Nine times out of ten, the failure lies hidden within—in the wrong interfacing or lining. These unsung heroes (or villains) of tailoring make or break a garment’s silhouette, durability, and comfort.

Choosing them can feel like a dark art. Facing a wall of fusibles and wefts, it’s easy to default to a generic mid-weight option and hope for the best. But interfacing and lining are not one-size-fits-all. The right choice is a precise engineering decision, balancing the weight, drape, and stretch of your face fabric with the desired hand, structure, and function of the final garment.

Based on over two decades supporting both bespoke tailors and large-scale uniform manufacturers from our base in Keqiao, I’ll demystify the process. This guide will give you a clear, practical framework to select interfacing and lining with confidence, ensuring your outer fabric always performs at its absolute best.

Why Can’t You Just Use Any Interfacing?

Think of interfacing as the skeleton and muscles beneath the skin of your garment. Its primary job is to control the face fabric—to add body, prevent stretching in stress areas, and create crisp shapes. Using a random interfacing is like giving a marathon runner the bone density of a bird; the structure will collapse under stress.

The consequences of a mismatch are severe:

- Too stiff/heavy: The garment feels like cardboard, moves awkwardly, and the interfacing may “grin” through the outer fabric at edges.

- Too light/soft: Collars roll, buttonholes stretch, pocket flaps wilt, and the garment loses its shape in hours.

- Incompatible shrinkage: After the first clean, the interfacing shrinks at a different rate than the face fabric, causing permanent puckering and bubbling. I’ve seen this ruin a batch of 500 corporate blazers for a client in 2023, where an un-vetted fusible shrank 5% more than the wool, leading to a costly remake.

The golden rule is: The interfacing should always be lighter in weight and slightly firmer in hand than the fabric it supports. Its purpose is to reinforce, not overpower.

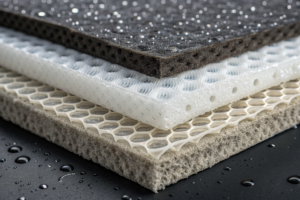

What Are the Three Core Types of Interfacing?

Your first and most critical choice is among these three families:

-

Woven Interfacings: Made from cotton, polyester, or hair blends (horsehair, goat hair). They are the gold standard for traditional, high-end tailoring.

- Best For: Suit collars, lapels, chest pieces, waistbands. They provide a natural, resilient structure that molds to the body over time.

- Key Product: Hair Canvas – a woven blend of animal hair (for resilience), wool (for loft), and often a viscose or polyester binder. It’s sewn in, not fused, allowing for unparalleled drape and breathability. It’s essential for mastering traditional tailoring techniques with hair canvas.

-

Non-Woven Interfacings: Made by bonding fibers together (like felt). They are isotropic (no grainline), inexpensive, and easy to use.

- Best For: Mid-weight fabrics, short-term structure, crafting, and areas where preventing bias stretch is the only goal.

- The Pitfall: They can be less durable and have a papery feel when handled. They are generally avoided in fine tailoring except for very specific, low-stress applications.

-

Knit/Weft Insertion Interfacings: These have a slight, built-in stretch (usually in one direction), making them ideal for modern stretch fabrics.

- Best For: Jersey blazers, stretch wools, ponte, and any fabric with Lycra/spandex content. They stabilize while moving with the fabric, preventing the dreaded “restriction” that a woven interfacing would cause.

How Do You Match Interfacing to Your Face Fabric?

This is the practical application. Follow this decision matrix:

| Your Face Fabric | Recommended Interfacing Type | Typical Weight | Application Areas |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heavy Wool Coating | Sew-in Woven Hair Canvas | Medium-Heavy | Full front, collar, lapel, hem |

| Mid-weight Wool/Suiting | Lightweight Woven Hair Canvas or Heavy Woven Fusible | Medium | Chest, collar, lapel, cuff |

| Lightweight Wool/Silk | Lightweight Woven or Knit Fusible | Light | Front facings, collar stand, hem |

| Linen/Cotton (Crisp) | Mid-weight Woven Fusible | Medium | Collar, cuffs, plackets |

| Stretch Woven (e.g., Stretch Wool) | Weft Insertion Knit Fusible | Light-Medium | Entire front, facings |

| Heavy Denim/Canvas | Non-Woven or Woven Heavy Fusible | Heavy | Waistband, pocket openings |

Pro Tip from the Workroom: Always test! Fuse or baste a 15x15cm square of your chosen interfacing to a scrap of your face fabric. Let it cure for 24 hours (if fusible), then test: drape it, crumple it, wash/dry-clean it. Does it behave as you want? This simple step is non-negotiable.

What Makes a Lining Fabric “Good”?

While interfacing provides structure, lining is the interior finish. It affects how the garment slips on and off, how it feels against the skin, and how the outer fabric drapes. A poor lining feels clammy, creates static, and wears out long before the shell.

A superior lining fabric must have three key properties:

- A Smooth, Low-Friction Hand: It must allow the garment to glide over other clothing easily. This is the slippage factor.

- Breathability: It should allow air and moisture vapor to pass through, preventing the wearer from feeling sweaty and trapped.

- Durability: It must withstand the abrasion of repeated wearing and movement against the body and other garments.

What Are the Standard Lining Choices and Their Best Uses?

The market is dominated by a few key players, each with a specific role:

-

Bemberg™ (Cupro): This is the luxury benchmark for suit and jacket linings. Made from regenerated cellulose (cotton linter), it is incredibly smooth, breathable, anti-static, and has excellent moisture-wicking properties. It’s cooler in summer and warmer in winter than synthetics. Its only downside is higher cost and a need for more careful cutting due to bias slip. If you’re looking for where to source premium Bemberg lining fabrics in bulk, this is a fabric we always keep in stock for our tailoring clients.

-

Polyester Linings: The workhorse of the industry. They are affordable, durable, and come in infinite colors and prints.

- Charmeuse/Satin Weave: Has a shiny face. Common in fast fashion and mid-market suits. Can feel less breathable and prone to static.

- Habitai/Twill Weave: A matte, fine twill with a soft hand. Offers better breathability and drape than charmeuse and is a great mid-point choice.

-

Acetate Linings: Often used as a more affordable alternative to Bemberg. It has a lovely luster and drape but is less durable, more prone to tearing, and can be damaged by certain dry-cleaning solvents.

-

Specialty Linings:

- Stretch Linings: Incorporate 5-10% Lycra for garments requiring extra ease of movement (e.g., fitted blazers, overcoats).

- Breathable/Moisture-Wicking: Often polyester with a functional finish, ideal for performance outerwear or uniforms.

How Do You Pair Lining with Garment Type and Fabric?

Your lining should complement, not fight, your main fabric.

- For a Wool Suit/Blazer: Bemberg is ideal. Its breathability matches the wool. Use a lightweight polyester habotai for a budget-conscious but still professional option.

- For a Silk or Linen Garment: You must consider cleanability and shrinkage. The lining should have similar care requirements. A lightweight Bemberg or acetate is often safe, but always pre-shrink.

- For a Heavy Coat: Durability is key. Use a heavier twill polyester or a ripstop nylon lining. Consider a quilted or insulated lining for winter coats.

- For Stretch Garments: Always use a stretch lining. A non-stretch lining in a stretch jacket will tear at the seams the first time the wearer moves.

A German menswear brand we work with learned this the hard way in 2022. They lined a stretch wool travel blazer with standard acetate. Within two months of customer use, the lining seams at the back armhole and across the shoulders had shredded completely, necessitating a full product recall and relaunch with a proper stretch lining.

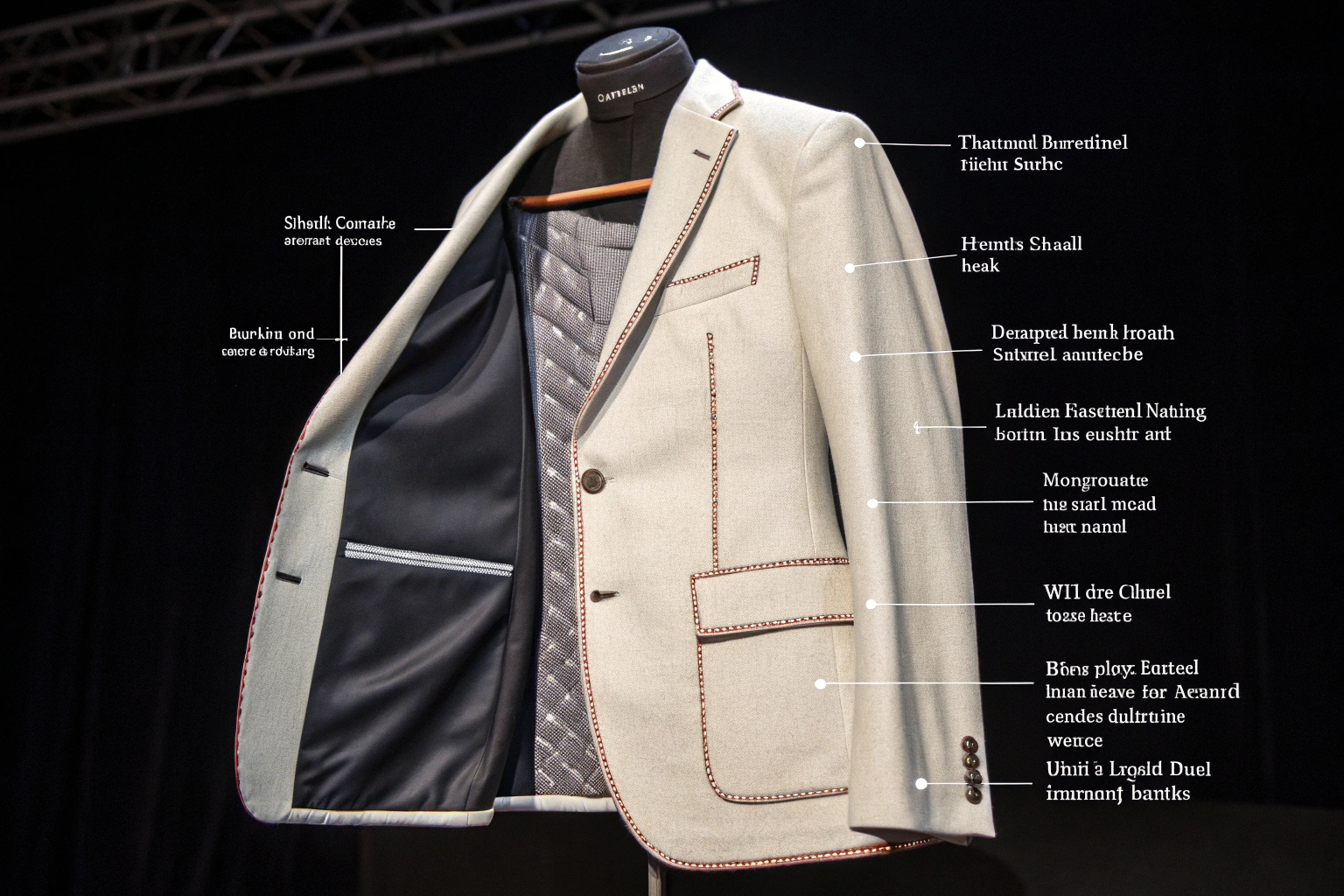

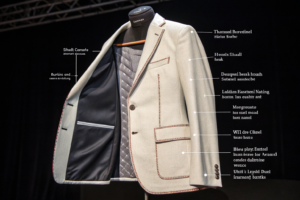

How Do Interfacing and Lining Work Together in Construction?

They are a team. The interfacing provides the localised structure, and the lining encases and finishes the interior, covering the interfacing’s raw edges and construction seams. In a classic jacket, the sequence is:

- The hair canvas is pad-stitched to the undercollar and lapels, and catch-stitched to the front facings. This is the “skeleton.”

- The lighter fusible interfacing is applied to the hem, cuff facings, and pocket openings for crispness.

- The lining is constructed as a separate “bag” and then attached to the jacket shell, elegantly concealing all the internal engineering.

What Are the Critical Application Techniques for Fusibles?

Most interfacing today is fusible. Getting the fusing right is 90% of the battle.

- Temperature, Pressure, Time: Every fusible has a “TPT” spec from its manufacturer. You must follow it. Use a professional fusing press with even heat and pressure. An iron creates spotty adhesion and shrinkage.

- Pre-shrinking: Always pre-shrink your fusible interfacing by steaming it thoroughly before cutting. This prevents differential shrinkage later.

- Grainline: For woven fusibles, always cut on the same grainline as your fabric piece. Fusing it off-grain can distort the entire garment piece.

- Cooling: After fusing, let the piece cool and set flat under a weight before moving it. This ensures the bond is fully set.

For anyone managing a production line, investing in proper industrial fusing equipment for garment manufacturing is not optional; it’s the single most important factor for consistent quality.

When Should You Absolutely Use Sew-In (Floating) Interfacing?

Fusibles are convenient, but there are times when sew-in is superior:

- With Delicate Fabrics: Silks, velvets, and loosely woven wools can be damaged by the heat and adhesive of fusing.

- For Maximum Drape and Breathability: A sewn-in hair canvas floats between the shell and lining, allowing the outer fabric to move and mold with a natural softness that fused interfacing can’t replicate. This is the hallmark of true bespoke.

- In High-Stress Areas: Some tailors believe the stitch attachment of a sew-in canvas is more durable over decades of wear than a fusible adhesive, which can degrade with heat and cleaning.

How to Source and Test These Critical Components?

Your face fabric supplier should be your first resource. A full-service mill or converter like Shanghai Fumao doesn’t just sell shell fabrics; we provide (or can expertly source) the perfectly matched interfacings and linings. This guarantees compatibility and streamlines your logistics.

Your Testing Protocol Must Include:

- Compatibility Test: As described earlier. Fuse/baste and observe.

- Durability Test: Martindale abrasion test for linings. Rub the lining against a wool fabric repeatedly to simulate sleeve friction. Does it pill or wear through?

- Care Test: Wash or dry-clean the fused/lined sample 3-5 times. Check for shrinkage, bubbling, adhesive bleed-through, and color transfer.

- Drape Test: Hang the tested sample. Does the shell fabric still drape naturally, or does it look stiff and artificial?

Always ask your supplier for the technical data sheet (TDS) for interfacings, which lists weight, composition, shrinkage rate, and fusing TPT specifications.

What Are Common Budget vs. Quality Trade-offs?

- Interfacing: The trade-off is between fusible (faster, cheaper, good for RTW) and sew-in canvas (slower, costlier, superior for bespoke/high-end). Within fusibles, heavier, woven fusibles cost more than non-wovens but perform far better.

- Lining: Polyester vs. Bemberg. Polyester saves 30-50% in cost but sacrifices breathability and the luxury feel. For a mid-market brand, a high-quality polyester twill (Habitai) is an excellent compromise.

Conclusion

Choosing the right interfacing and lining is the defining act that separates a home-sewn project from a professional garment, and a mediocre suit from an exceptional one. These hidden materials are the infrastructure—they determine longevity, comfort, and silhouette. The process is methodical: analyze your face fabric’s weight and stretch, define the structural needs of each garment section, and select the specialized interfacing and lining that meet those needs without compromise.

Mastering this selection transforms you from someone who assembles fabric into a true garment engineer. It allows you to predict and control how a piece will look, feel, and wear over time. In an industry where unseen details build a reputation, investing in the right “inside” materials is what makes your “outside” truly outstanding.

Ready to ensure your next tailoring project is built on a foundation of quality? At Shanghai Fumao, we understand that the shell is only part of the story. We provide comprehensive tailoring packages, offering not only premium wools and suitings but also the expertly matched hair canvases, fusible interfacings, and Bemberg linings that bring them to life. Let us help you engineer garments that stand the test of time. Contact our Business Director, Elaine, at elaine@fumaoclothing.com to discuss sourcing the complete material ecosystem for your next collection.